The most wonderful thing about Haines — whom you will perhaps remember for his story, “The Unnatural Encounters of Mr. Bergen,” published in Short Tales of Mystery and Suspense a week or so back — was that you knocked up against him in the oddest places. Never would you find Haines seated on the famous terrace of Shepheard’s Hotel in Cairo; but if you took your life in one hand, and a revolver in the other, and entered the dangerous slum district which skirts the citadel of the same city, it is ten to one that you would run into him sitting outside an obscure and oil-lit American cafe, having his boots cleaned, and reading a Greek newspaper with the utmost composure.

Yes, always you will find him at a cafe, sipping his beloved absinthe, be it in on a hill overlooking the Golden Horn in Istanbul, or Saint-Denis, an unpleasant suburb of Paris, or on the Rhinebank at Cologne, which is even more unpleasant.

However, a year or so after he had told me the story of Mr. Bergen, who he had known personally, in Marseilles, I met him again, this time outside the Dardanelles Cafe, which lies on the northern side of the Place de la Constitution in Athens. He greeted me with his usual friendliness, and, on my asking him if he had experienced any further eerie adventures since I had last seen him, he filled his glass and said: “Ever been in a place called Hajdúböszörmény?”

I looked at him in horror. “My dear Haines,” I said, “You surely don’t think I value my self esteem so lightly to allow myself to be seen in a place with a name like that? Where is it— in Cochin, China?”

”No,” he replied tranquilly, “in north eastern Hungary. You take the train from Buda-Pesth, jump off at Dobreezen, get on a nag, and after about twelve miles of rough going, you will land at the place with the awful name.”

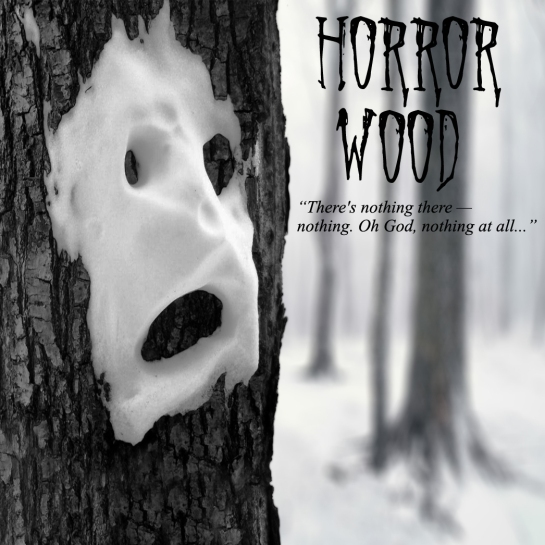

Haines lit a cigarette. “Between Hajdúböszörmény and Nyiregyháza,” he added, “lies a stretch of forestry which is known to the natives as Horror Wood. Here, old boy, have a drink…”

“I was passing through that part of Hungary about a year ago,” said Haines “with a fellow named Gilmour — a Scotsman, and an old acquaintance, Henry Gillespie. We had got talking to Gilmour after he had asked us for directions on a side-street in town and, before we knew it, had spent a thoroughly entertaining evening in his company, regaled by the tales of the highest scoring Scotsman in the Royal Flying Corps during the war. We had come right up country from Szedgedin, looking for oil, and our luck had been so bad that it appeared that we would go wandering straight into Czechoslovakia without finding enough juice to keep our cigarette lighters going.”

“Well, one evening we got into a tiny flea bitten village, whose name I shall probably be able to pronounce after about ten more drinks, and which was situated just on the fringe of this piece of timberland that the Hajdúböszörmén people had told us was named “Horror Wood”.

“Gillespie and I had made a bit of cash playing poker with the crooks in Debreczen, you understand, so that we were enabled to spend a day or two in this charming village of which I am now speaking. Interrogating the natives with an unnaturally good understanding of Hungarian, Gilmour found out that Horror Wood was so named because it was haunted by a most unusual ghost. The locals were too superstitious to describe the thing, merely stating that it was called the ‘Tree Ghost’ “.

“Sounds interesting,” chuckled old Gillespie. “I suggest we get out the nags and go and look it up.”

“That is not a bad idea,” replied Gilmour, with a broad grin! “If we sleep tonight in this village we shall be eaten alive by the fleas. I do not see that a ghost could do any worse to us than that. His blue eyes twinkled. “But I am taking my gun with me, all the same.”

* * *

“Horror Wood,” I said, as our horses crushed the thick vegetation under their hoofs, “seems to be a rather ordinary place, after all.”

“There is nothing here but the tall trees, the moon, and many mosquitoes. We have ridden three miles through this forest, and we have found little else.”

Said Gillespie with an effort at humour, “We aren’t out of the wood yet, friends.”

But we all felt depressed, riding there along the poorly marked track. It was absurd, no doubt, but so soon as we had entered upon the fringe of Horror Wood, our spirits had sunk into our boots. It was so silent, and the occasional cry of some weird nightbird only served to throw the universal stillness into stronger relief. Another half mile or so and Gillespie broke the silence: “I do not know how you feel, but I am tired. It would be best to throw down our blankets here and sleep.”

Nodding acquiescence, we brought our mounts to a standstill and were just about to start in settling down for the night, when there came a sudden noise of cracking twigs to our left.

“Hallo,” said I, “here’s the Dreadful Spectre at last!”

“Oh!” cried’ Gilmour, and raised his gun swiftly to the ready.

But it was no ghost, only a poorly clad peasant, who burst excitedly through the bushes, and greeted us with a torrent of hissing, sibilant Magyar.

“Go back” he almost screamed. “Go back quickly — at once!”‘ He swung his arm wildly in the direction of the moon. “The Tree Thing — it is riding tonight!”

We look, startled, into the man’s face; it was white as a sheet, reflected in the cold light of the moon. For myself, I felt an awful shiver run down my spine, and Gillespie and Gilmour, both brave men, look badly scared.

“What on earth is wrong with you, man?” barked Gillespie to the excited native.

The Magyar answered not, but looked fearfully over his shoulder towards the moon. And to our horror he let out a scream, which curdled the blood within in me, then dashed wildly into the direction from which he had come.

Then we three gazed upwards, as the native had done and what we saw, stood there as though rooted to the ground, fiercely trying to disbelieve the evidence of our eyes.

For above the tree-tops and suspended in mid-air, moved a something that at first sight seemed to be a wisp of cloud; yet possessing an uncloudlike solidity.

Gently and unerringly the thing moved, over the trees towards us, — and then, when the moonlight shone full upon — oh God! Believe me or not, as you like, but we three saw that night, a human form, dead and rotten, with hanging jaw and socketless eyes, move through, the air as though borne upon an invisible platform, above the trees of Horror Wood.

Suddenly I coughed and yelled. “We’re mad! We’re mad!”

The frightful phantasm was moving towards us.

“There’s nothing there — nothing. Oh God, nothing at all,” shouted Gilmour.

His gun seemed to spring to his shoulder.

A shot.

And, may I never speak again, if that awful spectre did not slowly crumple up and drift to the ground!

Overmastered by wild curiosity that was greater than even our terror, Gillespie and I, quite forgetting Gilmour, leapt from our saddles and dashed to the spot where the broken thing had fallen.

Quite beside ourselves, and still unaware that the firer of the gun was not with us, we bent over that which we had seen fall from the sky. And, the crumpled thing that we saw lying upon the ground was the dead body of our comrade, Gilmour. Gillespie said nothing, but looked up into the moonlight night. With a hand that seemed shaken with a palsy, he pointed towards the top of the nearest tree. Above it, floating like a wisp of cloud, and drifting very rapidly away from us, hung a thing that outlined the shape of a man, with a hanging jaw, and dreadful eyeless sockets. Gilmour was nowhere to be seen.